Vangeline

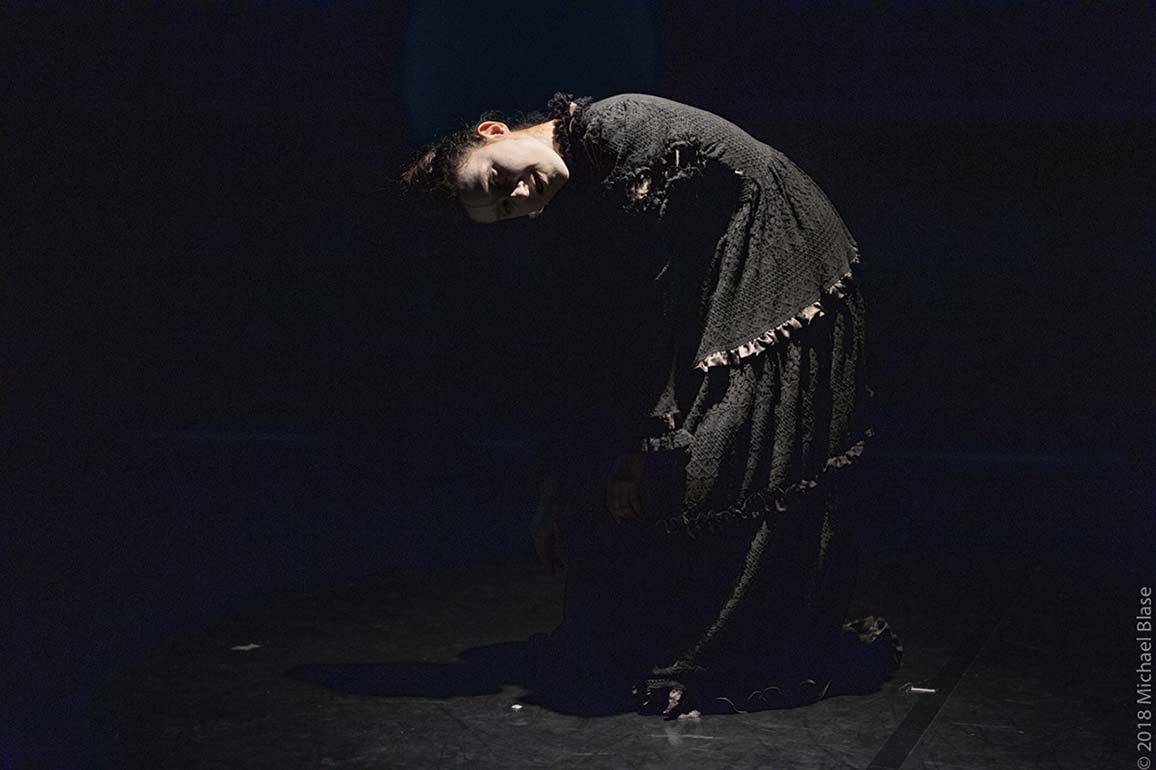

. . . her movement is extreme, almost absurd, slow, her eyes do not look out, they look inside, in a crossed vision of the body towards the soul. . .

What do we see? What do we feel?

. . . silent dance, grotesque theatre, improvisation, dancers painted in white, extreme images, expressiveness, search that goes beyond choreography, darkness. . . again silence. . . bodies that are filled with symbolism, pain, from the slow movement, we explore the metamorphosis of the body turned into dust, into wind, to penetrate into the subconscious that marks the rhythm. It does not seem necessary to understand but only to feel the movement. To feel the body while the dance of the soul takes place. . . again silence. . .

Is that it?

No, it’s not just that, it’s just the look. . .

舞踏

It arises in Japan, in the mid-twentieth century when they face the millennial Japanese culture with modernization and emerging industry, as a challenge to the conventional, a return inside to the root of the subconscious, to experience pain, darkness, to purify. The creators are the artists Tatsumi Hijikata and Kazuo Ohno. At first it is a marginal movement, rejected in the Japanese country itself where at that time the most praised and followed dance was western classical, being however successfully received in Europe in the 70s, after which, and in an artistic search in Japan for its own identity, is finally assumed as something proper, a cultural reference in contemporary dance, coinciding that moment in time with the expansion and popularity of Butoh promoted by artists who began to take it to Europe and the USA.

We spoke with Vangeline, director and founder of the New York Butoh Institute, and artistic director of the Vangeline Theater. She is a choreographer, dancer and teacher. It has been mentioned in the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times, among others. Her dance company is female, women only, social consciousness and activism.

We can highlight Vangeline among many other mentions that is the winner of Social Action Award Beth Silverman-Yam Gibney Dance in 2015Has participated in film projects that include a starring role with actors James Franco and Winona Ryder in the feature film of director Jay Anania, `The Letter” (2012-Lionsgate). She has recently been invited to perform with and for Grammy Award winning artists SKRILLEX and Esperanza Spalding; her work is the theme of CNN’s “Great Big Story”, “Learning to Dance with your Demons” and “Dance of Darkness”.

Vangeline, for those who only know that Butoh Dance is a dark dance, that uses slow, expressive movements, what could you tell us? How would you define it?

Butoh is a form of dance born in Japan in the 1950s. Butoh dives deeply into the unconsciousness of the body, and into the unknown; it returns and organizes the uncovered material through the filter of our conscious awareness, into creative movement. Butoh can be fast, or slow - speed does not define the art form, but rather its quality of movement makes Butoh unforgettable.

Dance or Theatre?

Butoh borrows from both dance and theatre; however, I consider that it is a form of dance because it is rooted in dance techniques.

Why do they say it's a dark dance, into the darkness?

Butoh is short for “Ankoku Butoh,” which means ‘Dance of Utter Darkness.” The founder of Butoh, Tatsumi Hijikata, coined this term. Hijikata wrote: “The utter darkness exists throughout the world, doesn’t it? To think is the dark”. We can presume that he meant that all human beings carry an unconscious and hidden side. Light and darkness are ubiquitous: when we dance butoh, we dive deeply inside ourselves, into the unknown. During this encounter, we grope into this mysterious darkness within and climb back into the light.

Butoh dance was born after the Second World War. How has it evolved to the present day?

Butoh has never stopped evolving or changing since its inception. There are many chapters in Butoh’s history; the early 60’s, a period of collective experimentations; the late 60’s, when a split occurred within the art form between choreographed and improvisational butoh; the late 70’s, when butoh left Japan and received critical acclaim overseas (starting in France in 1977); and between the 90’s and now, when butoh started spreading all over the world, which resulted in the emergence of cross-cultural or international butoh.

Why is white important in Butoh? Most of the performances I've seen include white in a relevant way.

Butoh has had very broad aesthetics over its short 60-year history. When we consider the breadth of Butoh expressions today, it is clear that the art form is not merely defined by its aesthetics. However, in the West, primarily due to Sankai Juku’s success, we have come to associate Butoh with specific aesthetics (white paint, cream-colored costumes, shaven heads, etc.). Yet the two should not be confused. Historically, at some point in its evolution, numerous dancers did start using white paint (after a phase experimenting with plaster). White paint is often symbolically used to “erase” our identity and dive deeper within. However, some dancers never wear white costumes or white makeup. Butoh is an avant-garde art form, which means that an essential rule in Butoh is to challenge the rules. Nothing is definitive in Butoh, certainly not costuming or makeup.

Is Butoh is a combination of organized dance and improvisation?

In the mid-60s, a split occurred in the butoh lineage. We can trace back techniques used by a butoh dancer to her or his teacher, who might have been trained either in the Tatsumi Hijkata lineage or in the improvisational lineage. To make a determination, it is essential to look back at the lineage. In general, the terms “choreography” and improvisation” are quite misleading when it comes to Butoh, for a number of reasons. This subject is complex (so complex, that I started writing a book about it). However, we can say, that, today, 3rd- of 4rth- generation practitioners are likely to have experimented with both approaches. It is possible that today, Butoh has become a hybrid.

Would you define it as a vindicative dance?

Although Butoh was rooted in the Japanese counterculture movement of the 60s, it has transcended its origins. As an in-depth exploration of what it means to be human, Butoh explores all aspects of humanity, the beautiful, and the ugly. To be human is to be complex. That complexity is apparent in butoh. Yes, many Butoh dancers have considered themselves to be on the fringe at some point or another (some still do), but Butoh is probably as provocative today as Modern dance was in the 20th Century. I prefer to consider Butoh as an art form, which encompasses a body of specific dance techniques. How each artist utilizes these techniques is up to them. To only politicize Butoh can be reductive and exploitative and is often representative of our Western gaze onto the art form. For example, we often encounter in the media a formulaic statement that “Butoh was born from the horror of Hiroshima.” This is a typical Western projection onto Butoh. These types of interpretations are very problematic, because they detract from the art form, and prevent us from viewing it as what it is: a serious and complex craft. Unfortunately, the phenomenon of projections around the craft of Butoh is significant. For example, because Butoh veers between consciousness and unconsciousness, audiences may perceive Butoh movements as provocative, or grotesque. But the dancer merely is dancing outside of the realm of socially accepted gestures. These gestures come from our nervous system and are as natural as breathing. Of themselves, they have absolutely no meaning. The audience ascribes meaning. Our teachers often say that, in Butoh, a good dancer becomes a polished mirror, so that the audience can see themselves. This phenomenon often reminds me of the Dark Ages. In the Middle Ages, someone could make a grimace or gesture, which was interpreted as “demonic” and end up burnt at the stake. Butoh has simply reclaimed this organic space of expression. In my case, it is true that there is often a political dimension to my work, but it does not mean that all Butoh dancers are activists, or that Butoh is “rebellious”. The art form goes far beyond battles. There exists a universal dimension to Butoh, which entirely transcends activism or feminism – it is about being human. Both can coexist. A great performance should confront and create unity at the same time.

The body seems to be very important in Butoh, more than in other dances, it gives the impression of great body feeling, very physical, What do you feel with your dancing, when you are acting?

Butoh is the crucible of body and mind. Butoh dancers train for decades to refine their mind-body connection. In more scientific terms: the relationships between the brain, the central nervous system, and the musculoskeletal system are of paramount importance in the craft. Butoh creates new neural pathways in the brain of its practitioners. The embodiment of Butoh is powerful for its dancers and equally compelling for its viewers. In the 21st Century, science is moving away from the Cartesian dichotomy, or separation between body and mind. Today, scientific research on embodiment can help explain the Butoh experience. In particular, the relationship between consciousness and embodiment is entirely unique to the art form. How does it feel like to dance Butoh? It is difficult to explain what a dancer feels like. Experiences are varied and also depend on the level of experience of each dancer. Again, the complexity of this type of question led me to offer a more comprehensive perspective in my upcoming book. I will be very excited to share my findings with readers when the book comes out.

Tell us about your all-female dance Company, all women, it sounds very interesting, and in fact, we are very interested in it.

The Vangeline Theater is an all-woman butoh company. Between 2002 and 2017, I have choreographed mainly for women. For the past two years, I have been focusing on my solo career, while organizing a Butoh Festival in New York featuring female butoh artists. From the beginning, I was interested in the female expression, and in female bodies. On the one hand, Butoh offers tools for women to break free from the “beauty myth” and societal expectations, but on the other hand, it is also a male-dominated art form, which has been quite oppressive to women. I am committed to featuring female Butoh artists, who are under-represented and have had fewer opportunities than men. Featuring female artists sends the message that women are worthy of critical attention. It slowly reshapes the public perception of this art form. On a personal note, I simply find women compelling, because they are more adept than men at diving into the mystery of life. Women are fundamentally creative and plugged in.

We are also very interested in your opinion about women and the world of arts in general.

Women have been oppressed for thousands of years. We are overworked, underpaid, and underrepresented artistically. Statistically, we are also the victims of men’s violence all around the world. Patriarchy runs very deep. As a group, we still need to learn to put other women first. I am hopeful that the world is changing. But nothing scares me most than complacency and assumptions that things are always getting better for women - by default. In many cases, rights that our mothers and grandmothers fought for are being eroded or taken away from us. We need to remain vigilant. By creating work, I fight for myself and therefore for all female artists. A woman artist is, by definition, an activist. Every time a woman is seen, heard, and has an impact; she opens the door for hundreds of other women.

What are your artistic references, those masters that inspire you?

I grew up in France in the 70s an only moved to the United States in 1993. I draw inspiration from my cultural heritage, but I have also been influenced by my work and collaborations in the underground New York scene of the 90s. I was part of the burlesque revival movement in New York and have performed for the Jackie Factory for decades. New York scene was an incubator in the 90s; I was exposed to true renegades, originals, innovators, artists who were the best in their fields. I have had the chance of making a living practicing art and dance since 1993; I also worked in fashion as a makeup artist for visionaries such as Isaac Mizrahi. Every detail always counted – this teaches you to always do your best. I have also been very inspired by Butoh Masters I have had the privilege of working with for the past 18 years. Every Butoh performance I attended has been a gift. Because Butoh dancers carry the imprint of their teachers on stage, Butoh is like a time capsule. The Past fascinates me. I am drawn to historical costumes, and often feel that the past can dance through me.

In your artist statement you talk about symbolically offering others a vision and a statement about that which we are, a journey into ourselves. You say: “Butoh can lead us back to our rebellions, our private wars, our wounded selves, and through the process brings what is hidden into the light, that the process is deeply healing and transformative. We become more capable of intimacy. We can be fully creative. Butoh can take us on a path to embracing ourselves fully, transforming our Shadow, finding beauty and strength from the depth of our fragility. This transformation comes from holding a mirror to each other and integrating our many facets- the beautiful and the ugly; and from reintegrating the forgotten of our society into our midst” Woww, is it possible to explain that here for us?

To understand this, one has to experience Butoh. I would say, come take a class! Butoh is transformative work, but it is a concept until you have experienced it.

Tell us about your next performance in May of this year.

I will be performing ɪˈreɪʒə (the phonetic pronunciation of Erasure). With this piece, I summon up the spirits of women who came before me. Women are the forgotten of history. We have been silenced, erased from memory; even our names have been erased, while famous men were laid in the Pantheon for posterity. How many women writers, artists, scientists are there, whose names we will never know or remember? I am forever in mourning for this tragic loss. Through the magic of Butoh, I will “erase” myself, and give space for women to come back and dance through me. The performances will take place between May 15-19, 2019 at the beautiful, spacious and historic Theater for the New City in the East Village. I am very excited to dive again into this solo, called Elsewhere in 2018 and commissioned by Surface Area Dance Theatre in the U.K. in 2017. In May 2019, ɪˈreɪʒə will feature brand new lighting, music, and choreography.

What message would you like to convey to women in the world of art, dance in particular?

Nurture your confidence and trust yourselves. Never second-guess yourself: when you shine, you inspire another woman to take her place in the world. Finally, challenge our collective memory; when you remember other women, you will be remembered.

Jo García Garrido