Graciela Iturbide

Not long ago, I personally interviewed Graciela Iturbide, and given that she will be awarded the Spanish Princess of Asturias Award for Arts in 2025, I would like to republish that interview. According to the Princesa de Asturias Awards Jury's minutes, "it is unanimously agreed to award the 2025 Princess of Asturias Award for Arts to Mexican photographer Graciela Iturbide. Possessing an innovative vision and endowed with extraordinary artistic depth, Iturbide's lens has portrayed human nature through photographs charged with symbolism, creating a world of its own: from the primitive to the contemporary; from the harshness of social reality to the spontaneous magic of the moment.

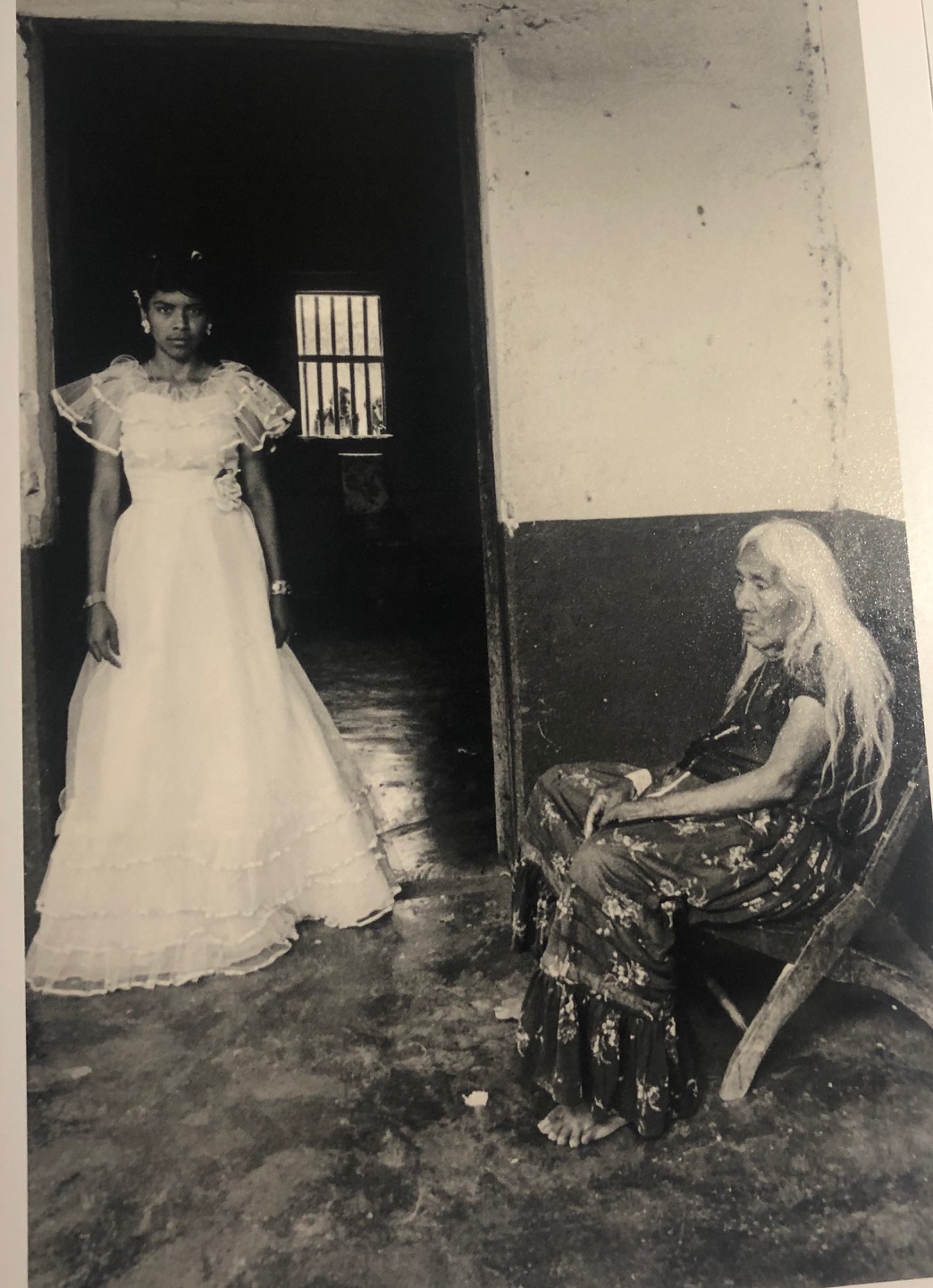

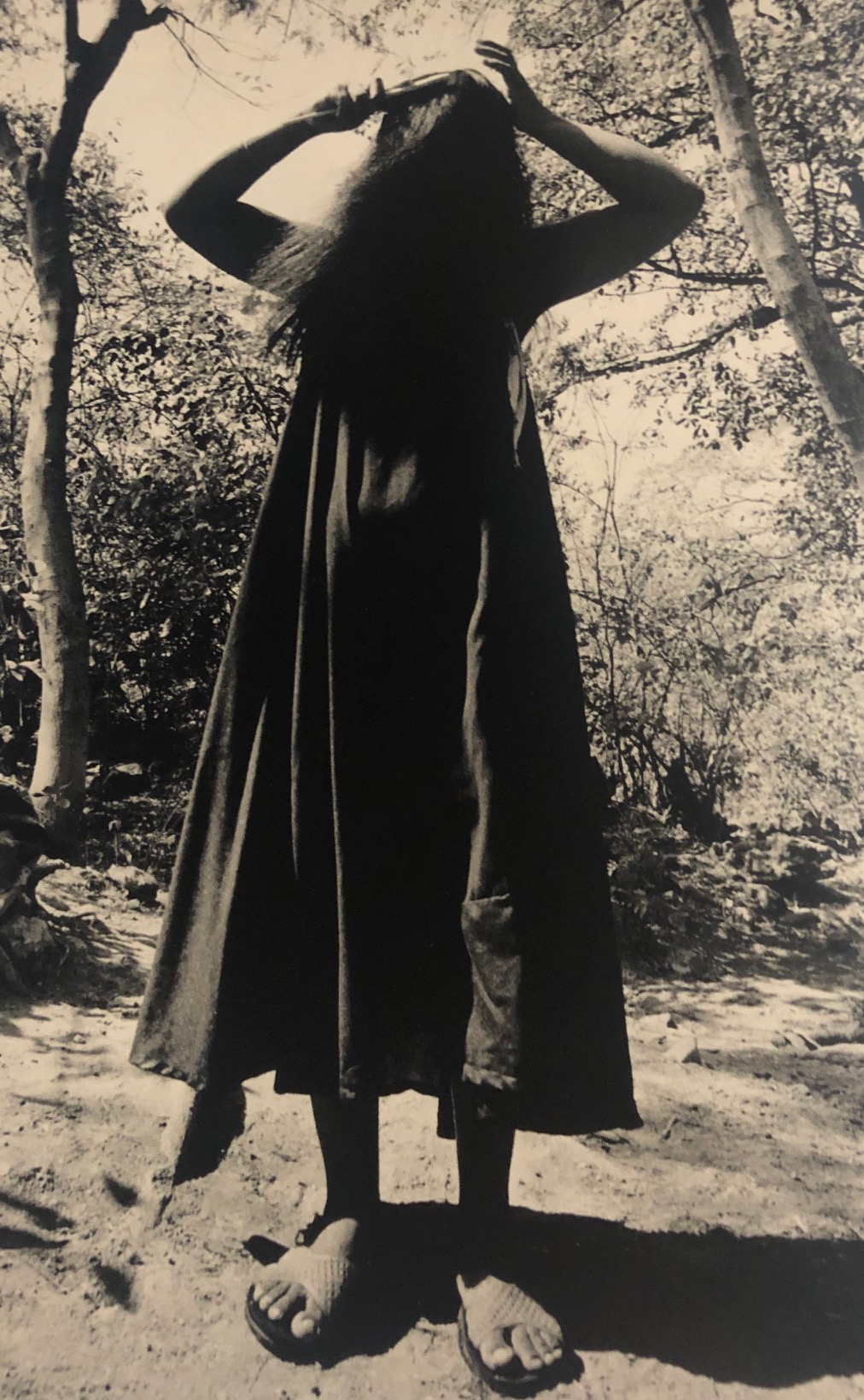

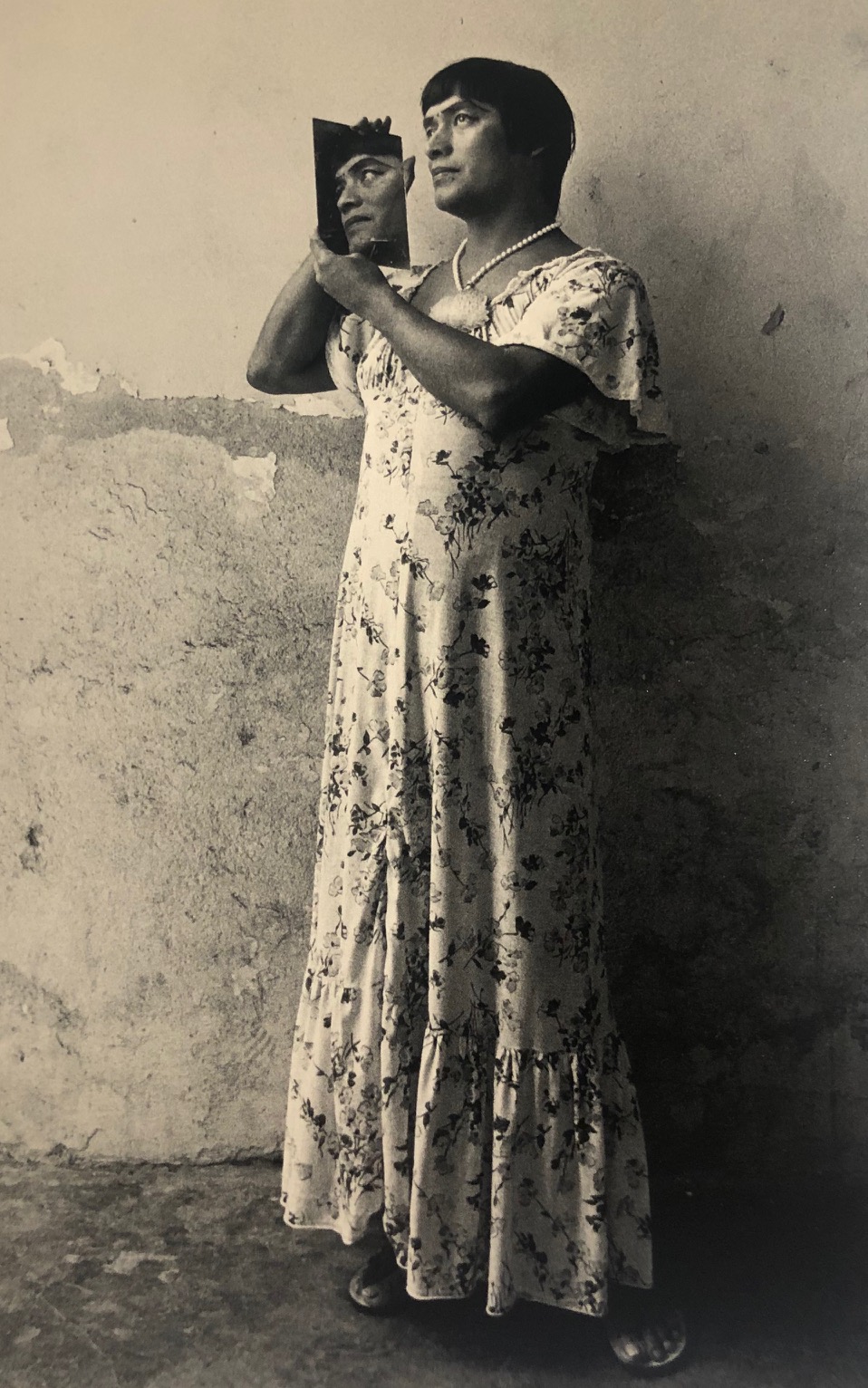

Graciela Iturbide's black and white work combines a documentary sene of the image with a poetic one. Through her camera, she captures daily life in Mexico with a profound, respectful, and evocative gaze. Her images show not only what she sees, but also what she feels. Each photograph carries an emotional and cultural charge that invites us to look beyond what is visible." We are happy to share the interview

Gabriela Iturbide, born in 1942 in Mexico City, began her studies at the Centro Universitario de Estudios Cinematográficos of the Universidad Autónoma de México since her intention was, at the beginning of her professional aspirations, to be a film director. However, at the same university, the photographer Manuel Álvarez Bravo taught classes for whom, attracted by his work, she ended up working as his assistant. And that personal and professional relationship changed her artistic life with no apparent turning back.

Shortly thereafter, in the 1970s, a professional career began in the world of photography through human landscapes and traditions, especially in Mexico, a country of pluralities and contrasts. Since then, her photographic work has been internationally recognized and applauded during her travelling in that country, her native country. It is worth highlighting her photographs of the Seri people, the nomadic fishermen in the Sonora desert and the town of Juchitán; these women, the matriarchy that characterizes him, and the muxes, part of Zapotec culture. All of them document the customs and traditions of the country’s indigenous population. A look at Mexico from the point of view of a Mexican woman, from a sister understanding, especially of women, their traditions and their power that escapes the superficial and foreign glances of that culture and that Gabriela Iturbide knew how to capture and transmit, like the spirit of Frida Kahlo that reaches us intensely through objects, those that conformed her bittersweet and intense existence, captured in snapshots of a realism mixed with a symbolism that allows us to perceive life in inert objects. That’s what this woman, this artist, transmits to us.

Also between 1980 and 2000 her travelling took her to different parts of the world: Cuba, India, Madagascar, Hungary or Paris, producing an important and interesting photographic work.

On Mexico in particular, the exhibition “Graciela Iturbide´s Mexico” is now being held from January 19 to May 12 at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. The exhibition includes 37 recently engravings.

Photography is having a passion for wanting to see, and when it comes to someone like you, with that intense photographic work captured in your travels around the world and especially in your native country, Mexico, I wonder if that way of seeing, and of capturing realities, that passion for looking beyond, changes if it is about your own country to when you travel the world as a “foreigner”. I guess it's not the same to see from the inside as to do it from the outside by digging inside.

In the beginning, when I began to photograph, I dedicated myself to travel through my country to indigenous areas, to the festivities of my villages, in this way I was learning about the culture of my country. I think the eye and heart of a Mexican woman doesn't change when she travels, because the surprise you get when you travel is the same as in your own country. Besides, one is formed in such a way with what you have read and heard, photography can change for the places you visit, but the look doesn't change.

Your photography gives us an opportunity to get to know the human being, bits of his customs take us into a “something” beyond. Is there a premeditated search for knowledge of the human being in your work or is the camera given to you as if by chance? I'm referring to the fact that there is a difference between what the eyes see with and without the camera. Is there such a difference?

Yes, there is a difference. The eyes see first and so there is surprise and that's when my camera acts. However, I'm going to give you an example of when I did the Slaughter of goats. Without the camera, I couldn't have done this work, as it was very hard, and somehow, by seeing all these scenes, my camera protected me from killing, blood, etcetera, etcetera. Another example is when I went to Juchitán to work, living with people of Zapotec origin, where I shared both in the market, as sleep at home and enjoy their parties, the situation changed. When I was with these women in their community for so long, I was constantly observing and being impregnated with their rituals, all this helped me to have a close relationship with them and the complicity of this people and in this way, I was able to reflect a little more and photograph in a calmer way.

Do you work with previously organized projects or do you go out looking for what the world and the camera want to give you?

Usually I go out looking for what the world and the camera want to give me. In the situations in which I have a project, surprise also acts but with a greater knowledge of the culture of these people. In the case of these projects I don't prepare anything, I read a lot about their culture and above all, I learn from these communities, but I always let the surprise work. In all cases, if I'm not surprised, I can't photograph, I never take a picture just as a testimony, only when the emotion is produced in me.

In your photography throughout all this time Photography as a historical document or as a claim? Perhaps photography only as art?

I don't intend to leave a testimony, nor that my work is artistic. Just like I said before, imagination and surprise act. In my projects, I interpret the world and let the public interpret my work. There is a phrase by Dante that says, “imagination is the deep well where fantasy arises”.

Have you experienced pain in your travels through the villages and their people?

Sometimes yes, it depends on where you go. But in general, Mexico and its people are generous and accept you in a warm way. Of course, in my country there are very marginalized places, but I try not to photograph poverty, I always want to give human beings the dignity they deserve.

Some photographers, especially those who live through wars and armed conflicts, have been accused of doing aesthetics with the misery and pain of others. Do you share that approach? Where are the limits? What part remains in intimacy? And at the same time, I wonder if for some reason there are voluntarily unpublished photographs.

There are war photographers, such as Gerda Taro, who have dignity in their photos and make with their images that we have a worthy knowledge of what is happening, no matter how strong.

What about yourself in your photography? What have you taught photography after so much time devoted to it? Is there anything in your life that would make you see your life and the lives of others in a different way? Something that marked you in a special way?

As I have always said, the camera is the pretext to know the life and culture of the world. Of course, all these experiences that I have had have made me mature and understand what is going on around me.

Has any photographic report presented you with a moral problem?

When it comes to my work, I'm very careful to respect what I photograph. In this way, I have never had a problem that causes me or others to lack dignity in my work.

In your photograph “Héroes de la Patria” taken in 1993 in Cuetzalan, Puebla, Mexico and which is part of the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, we see history, way of life, aesthetics and to which it seems the true hero as the protagonist, What is the history?

As I said, it was the surprise that made me take this picture. In Cuetzalan, Puebla, I accidentally went up to the Mayor's office and found this peasant waiting to be taken care of, coincidentally together with these portraits of our heroes. Evidently, he's the hero of the homeland.

The photograph titled “Nuevo León" taken in Mexico, what does it tell us?

In the north of Mexico, in Espinazo, a ritual is celebrated every year that has to do with the child Fidencio. This boy healed with his hands and even some president of the Republic went to see him. This ritual is that the child Fidencio (who died long ago) comes down to help his followers, these followers are called “cajitas” and heal in the same way that he healed all people who came from all over. The photograph to which you refer is in a spring where people come to purify themselves. Afterwards, they go to the place where the “cajitas” (the people who heal) are. I've only been there once and was so impressed that I've never printed the photographs I took that time.

At the death of Frida Kahlo in 1954, Diego Rivera decides to close two bathrooms full of objects belonging to the Mexican artist, which finally, in 2006, open again. And to testify about what is contained there with the logical expectation of the event, you are invited to be the one to give graphic testimony about Frida's personal objects, which every day is a little more legend. In these two photographs two different corsets are shown whose only image transmits us pain and discipline, endurance. Tell me something about that experience, which you felt. Things, personal objects always speak of the life of their owner, and when it comes to that house, that of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, I imagine it was something special, an experience and feelings that end up showing your photographs.

I'm not a Fridomaniac. Frida to the public is already a saint. But when I walked into that bathroom and saw all those painful objects, I rearranged them in the bathroom to do my job. It was very strong to be in contact with all these objects locked up for so long. To work with them, I admired Frida Kahlo for all the work she did as a painter with so much pain and I admire the therapy she had as a painter despite the pain she had.

In your travels through Mexico you show us the ordinary life of the inhabitants of the different villages and their customs. Often there are photographs of lifeless animals in contrast to their people as we observe in the photograph of “El viaje de Tlaxcala” taken in 1980, in “Pescaditos de Oaxaca” in 1997 or in the more recent “Pollos de Colombia” in 2018, the latter image that conveys identity and a strong intensity. Do they share any symbolism?

I photograph what I find and again the surprise works. Sometimes I don't know why I take certain types of photographs, but when I see them, I love them and record them.

The people of Juchitán awaken a special interest for their special customs, their idiosyncrasy, their roots and traditions, which have been talked about at length. Women in particular. This photograph of “Los Pollos” taken in 1979 is especially shocking, it is the image of death as part of life, there is death and at the same time humanity. What could you tell us about it?

I was working in the market with the local women. I saw this lady with her animals pass by this wall that looks like blood but curiously is paint on the wall, what one sees is simply symbolic. In this case, life gave me an image that has to do with life and death.

If possible, would you put music to a photograph? Which one? Which music would you choose?

I have a book called Asor, where my son who is a musician made a composition to accompany this book. I don't feel gifted to put music to my photographs.

In the photograph entitled “Oficina de la policía de Oaxaca" taken in 1977 the objects that appear, male berets and a typical calendar of the time very in the macho style of the moment, and yet contrasts with that matriarchy and respect for the woman of the town of Juchitán, a place in the same state. It's an interesting contrast. What did you want to show with that snapshot?

I was just in a town in Oaxaca called Tuxtepec, not in Juchitán, I went into the office, was surprised and took the picture. But I never saw the calendar, until now I realize, that happens often, I take a picture and even a long time later I see other things. Is it intuition?

How has Mexico changed since you took these photographs?

It has changed a lot and for the worse. I can no longer go to many places because there are drugs, kidnapping, it makes me very sad, because I would like to be able to continue working in my country.

When you enter a culture and that experience, I wonder if your condition as a woman has opened or closed doors for you, because what I perceive as an observer is a lot of closeness to people, and it seems so natural, almost an integration, as if you were part of those people.

When I work, I need to have complicity with people, fortunately I have never had any problems as a photographer, on the contrary people help you.

That men and women are different when it comes to perceiving sensations and transmitting them is something that is often affirmed especially in the world of the arts, do you agree? Do you think there is a special sensitivity of women in the world of the arts? Is it a way of seeing, perceiving and, therefore, transmitting differently?

Unfortunately, I don't know, since I don't know the sensitivity of man. In my case, as a woman, I've had the necessary help. Now, I know the work of male photographers with a sensitivity similar to that of women. Or vice versa, I know female photographers that their work is very strong and may seem like the work of a male photographer.

There is also sometimes talk of machismo in the world of photography, where the majority of photographers are men. What would you say to women photographers who want to make their way in the world of photography?

In Mexico, there are many women photographers, including war journalists and all excellent. I have not suffered machismo because I work alone in indigenous communities where men and women respect me.

I would like to know your opinion about the world of photography today, now that everyone seems to want and be able to photograph and where image seems to have become the universal language, that world of mobile phones with sophisticated cameras, this world of Instagram

Photography has always been very democratic, we always have family albums, portraits of loved ones that adorn houses. As for mobile phones, by chance, there are professional photographers who have made exhibitions on this digital media. It all depends on the eye of who's behind the camera. Or you have to take into account that people who have a cell phone have fun taking what they see around them or the famous selfies, which I think is exaggerated. I see Instagram frequently, but I try to see the work of the photographers I like.

It is curious the different conception of photography and the realities depending on the photographer. An example of this is your photography “El Fotógrafo"; taken in San Cristóbal de Chiapas in 1980.

I repeat once again that photography is democratic. This man who is photographing in Chiapas lives off his work and I saw several people waiting to have his portrait. In the villages, at that time there was little means of photographing. This was one of them.

We often hear that the natural evolution of a photographer is video, or cinema, which despite being different disciplines leads to each other. You started studying cinema and I imagine it was because of something that led you to it, an attraction to that other brother world. We know that your teacher Manuel Álvarez Bravo had a lot to do with that change that marked your artistic life as you yourself write in your biography. But I'm interested in knowing whether cinema still has an influence on your photographic work, or whether you've ever thought about making films after having decided a long time ago to move away from it. Do you think there's an evolution from one discipline to the other like a circular path?

Both cinema and photography handle the image, I was attracted to studying cinema by all the films I had seen in my life, Fellini, Pasolini, Italian neo-realism and there are some works of art in cinematography that have influenced me to be a better photographer, for example, Tarkovski. For now, I'm happy to be able to travel with one or two cameras around the world. Making films that I would love to make involves a lot more work in terms of cameras, lights, equipment, and so on.

If you couldn't photograph, what artistic discipline would you choose? Or maybe there's no plan B. . .

I'd be a writer, who I always wanted to be.

Returning to photography and as something more general but interesting from the point of view of capturing reality, of documenting it. Why black and white? Analogical or digital?

I also photograph in color, but when I have black and white film, I see life like that, in black and white. Analogous because it is my ritual and I love to see my contacts and have the time to choose.

What is left for you to do after such an intense journey during your artistic career? Is there any new project in your path?

Photography.

What photograph of all your work would you keep if you had to choose only one?

I can't choose just one, they're all my daughters, good or bad but I want them.

I would very much like you to tell us the name of a book, a piece of music, a dance, an artistic work, a cinematographic piece and a photograph, which are significant for you, appealing to your sensibility.

La Virgen del Parto by Piero della Francesca and Nostalgia by Tarkovsi.

We cannot finish without remembering that Graciela Iturbide’s work has been the subject of exhibitions at the Centre Pompidou (1982), the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (1990), the Philadelphia Museum of Art (1997), the Paul Getty Museum (2007), the MAPFRE Foundation, Madrid (2009), the Photography Museum Winterthur (2009) and the Barbican Art Gallery (2012) . . . among others. And from January 19 to May 12, 2019 at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston the exhibition “Graciela Iturbide´s Mexico”.

Her work is part of the collections of museums such as MOMA New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York or Los Angeles County Museum of Art among others.

Jo García Garrido